The life of a car nut behind the Iron Curtain

This story is something quite different. It’s a great read and gives us an insight into the life of a car nut behind the Iron Curtain. I Know Sergei’s Granny would have been a fascinating woman to have met. The journey across Siberia in her Moskvich must have been gruelling but what an amazing adventure she and her husband must have had. Thanks Sergei for your brilliant story of a young Russian Car nut.

Back to our subject, I want to tell a story of my grandmother’s Moskvich 408 / 412, an example dubbed in its later life as a “silver bullet”. The type was first shown in London’s Earls Court in 1964, and since then it was sold in Europe and served as an affordable base for conversion into race and endurance competitions of all kinds. M-408 driven by Tony Lanfranchini became a UK Saloon Car champion back in 1972. I found some photos in the net, one from 1972 UK championship published by Lancaster Insurance UK, another from Spa 1971 race, (found at DoubleDeClutch.com blog). Besides the main factory in Moscow, the type was also built from kits in Belguim and Bulgaria. Eventually more than a half of all examples were sold outside the USSR, who was keen to get currency inflow and happy to export something. That was well before all the oil and gas pipelines.

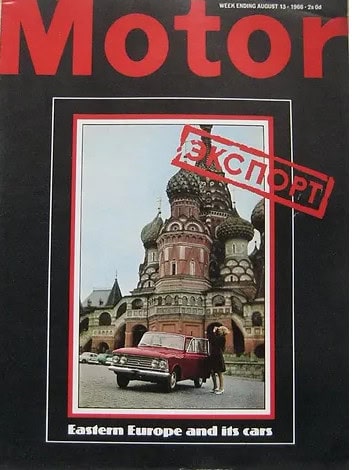

Moskvich 408 was pretty well designed, with front and back crumple zones and safe steering column, seat belts and two-circuit braking system. Motor magazine tested the type in August 1966, comparing Moskvich with Morris Oxford Mk 6 and claiming it as “a lot of car and equipment for its price”.

My maternal grandmother Anna bought the car in 1974. Granny was a fearless lady who in the 70’s ventured to work as a cooperative sales supervisor in Magadan on the Pacific coast. A port and mining spot, place of fascinating nature and horrible history. The land holds immense deposits of gold and other minerals. Those were mined by slave labour in GULAG camps in the 30’s, which predetermined the way people lived there after. In the 70’s, as my story goes, it was still a rough area, significant part of the public being either proper criminals or so called “enemies of the people” released and rehabilitated after the death of Stalin (yes, I liked the film). Free movement and resettlement of those folks into the central part of the country was all but banned, but those who volunteered to go in the opposite direction typically gained three times more in salary. Jobs in The North and Far East were hence used as a fast track to become rich by spending few years of life in a hostile and scary environment.

Once the Union collapsed in 1991 the area was nearly abandoned by the central powers and has by now depopulated by as much as 57%. Pure mother nature. In the 70’s it was a very rare case to have a driver’s license for a lady. Still, Granny Anna fared well and got hers on the event of car purchase, in November 1974. Life on the fringes as I mentioned above, had its benefits. Cars for example were faster to acquire (not that 10 years waiting list), so she ended up having a sand-beige saloon in the best possible trim – an export facelift version of Moskvich 408 IE. Lots of chrome-plated parts, cabin trim in orange brown vinyl. The smell inside was an absolute joy, especially during a hot day. Characteristic rectangular headlamps (by the way, made in East Germany) were quite a feature for the cars of the early 70’s, so the car looked romantic and modern. Space age. The engine was a weak 1357 cc, 50 bhp straight four. It still utilised bits and pieces from a cast iron cylinder block of the 1938 Opel Kadett, as whole Opel production line was moved from Germany in reparations after the war and installed in Moscow (MZMA factory as it was called back then). Cylinder block was remarkably similar to BMW’s M10 series, being slightly inclined to allow for intake manifold and two-barrel carburettor. Alas, it was still an ancient OHV cam (with funny rocker arms and push rods) which determined its phlegmatic character. Suspension was typical for its day, with sturdy double arms in the front (by their look, those could have been installed in a tank). Leaf springs were supporting whining and leaking rear axle in the back. Back to my grandmother, by the mid-80’s she packed up and started her move back to the central Russia. My family and I then lived in Kaluga, South-West of Moscow. Many former Magadan residents have moved there in the 80’s, so it was a natural choice for my grandmother as well. Amazingly, she (with her husband in passenger seat) drove large part of the way (and by the way it’s a 10,086 km distance through Siberian plains and woods). Most of the road was either seasonal dirt track or in best case, gravel. Once she reached the “spine”, a trans-Siberian railway, a few thousand kilometres after she started, the car was loaded into a container for the final part of the journey.

When I saw it in 1981 I was fascinated by its breath of heat, and smells and noises it emanated. It had just over 20,000 miles on the odometer, though after 6 years in the middle of nowhere and especially after the latest rally trip to civilisation, some of the exterior panels and décor looked quite battered. Granny lived separately, commuting between her apartment and summer cottage, so the car hasn’t been driven by my dad except for some odd occasions. In fact, it stayed in a detached garage block for the entire time, waiting. This allowed me to develop a habit of nicking garage keys from my dad from time to time, take my school chums and embark on a bus journey across the town to the garage. I would open gate fast, sneak in and stay there quiet, not to be seen by garage staff. That gave the whole enterprise an extra flavour. I was able to sit in a car, adjust mirrors, touch levers and push buttons, open its bonnet and observe the oily tubes and wiring. What an adventure for a 10-year old boy. Fast forward to my adolescence, the year is 1996. Moskvich resides in its garage, still very rarely driven, but time starts to take its toll on it. Front springs cracked by rural tracks and heavy loads, ball joints rattling, engine leaking oil and transmission howling for service. Eventually I asked my granny to allow me to revamp the thing so that it would look and drive decently. Plan was to restore and leave the car to myself as a collectable. The first part of that plan went well indeed. I stripped the car, opened and cleaned the engine, changed rings and bearings and seals, nearly all its suspension and steering joints, shocks, front bumper and countless bits and bobs. My friend, who was running an amateur garage and body shop, agreed to spray the car on condition I do the prep and sanding myself. And so instead of reproducing the original sand beige acrylic, I chose a premixed pale green-gold metallic offered by Sikkens. Once the car was back on the road, it was dubbed silver bullet. Thing looked pretty exclusive in and out, particularly because of its fresh look and colour, as most of cars of that age were used mercilessly and normally moved sacks of potatoes and veg from farms.

I must admit that it was far from being fast or furious. Brakes were particularly terrible, those “drums”. Adjusting braking shoes and springs was a regular torture, and acceleration seemed like calling the dead to raise to a battle. I’d say, it was much better as a static exhibit. The ride quality was on the contrast, an utter comfort (unless you dare to turn from a straight line). For all my life I haven’t seen any other car so soft and comfortable as that old thing residing on fat 13-inch rubber. Life was galloping so when I took a good job after graduating the uni I abandoned a dream of cruising in an oldtimer and bought something I could actually use as a daily car, first an Ascona (or, as it was called in the UK, Vauxhall Cavalier series II) and in 1998 getting a red BMW E30 with all its fun and M-tech skirts (though powered with a humble 318i).

The good old Moskvich stood still again before my grandmother, who retained the title all along, needed money for a building project and sold it to the very same friend of mine who earlier helped me with the paint job. He changed the engine to a more decent 75 bhp version, and finally sold it to someone through a local newspaper ad (no internet those days, remember). Though I hardly made a thousand miles in a silver bullet, the whole adventure helped me to gain a taste for a classic car as a concept. I remember Moskvich with warmth and a bit of sadness for the long gone years of youth.